|

|

An Internet Prayer Wheel

Nature does not know extinction.

All it knows is transformation.

Wernher Von Braun,

Quoted on the title page of

Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow

Nain Singh walked twelve hundred miles in the employ of the

British Secret Service. Dressed as a pilgrim, he was dispatched

to survey the road to Lhasa. Singh was specially trained to

walk every pace at exactly 33 inches. His pilgrim's rosary,

on which he counted several million of those paces, was used to

click off the distances. The rosary had only one hundred beads on

it, instead of the sacred 108, and if any of the numerous guards,

police, and customs officials had bothered to count he would have

been instantly killed.

Singh's pilgrim outfit had a few other special modifications. His

tea bowl was used to hold mercury to find the horizon. His walking

stick held a thermometer, which he would dip into the tea water

just as it came to a boil and thus determine the altitude.

The biggest sacrilege, though, was Nain Singh's prayer wheel. A

prayer wheel is a holy object containing the

Tibetan mantra "Om! Mane Padme Hum!" ("Hail! Jewel in

the Lotus!")

written many

times on a scroll of paper. The scroll is put inside the wheel,

and when it is spun the prayers are sent upwards.

In Lhasa,

and later in Dharamsala, huge prayer wheels will contain a

million prayers, all sent with a spin of the mighty discs.

Inside Singh's prayer wheel was his route survey, careful notes that

showed the altitudes, the landmarks, and the distances that

he walked. The route survey was brought back to Dehra Dun where

Captain T. G. Montgomerie, the man who hired Nain Singh, was

building a map.

The maps of India, indeed the maps of much of the world,

were built by such linear route surveys. A man on a horse

would be sent out in one direction and told to write down

the distances he traveled, any landmarks, and any other

significant information.

Back at headquarters, the route surveys would be collated

together and slowly, maps of the country would be built.

Later, the process became more systematic with the Great

Trigonometrical Survey of India, a massive undertaking

that established well-known points of latitude and longitude

and then gradually built triangles between the points until

a full map of the coast and interior of India had been

built.

The explorers, especially the romantic heroes such as

Singh, are the ones that we often remember, but it is

the process of collation and coordination that makes

the exploration possible and real. For every Nain Singh,

a Captain Montgomerie is needed.

|

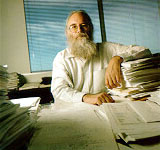

Remembering Jon

|

|

|

A silent and invisible tribute to the late

Jon Postel |

|

|

|

|

|

When Jon Postel, the Editor of the Internet RFCs passed away,

I spent a long day thinking. I don't know why, but I immediately

thought of prayer wheels and explorers. Jon was the creator

and maintainer of the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA).

While many people became rich and famous from the companies they founded,

it was Jon more than anyone who could lay title to creator

of the Internet. (Of course, doing so would be unthinkable

to Jon. He was always modest and circumspect—yet always passionate

and stubborn—in his beliefs.)

The IANA was the point that made the Internet possible. Here

was the registry of the known protocols, of the numbers that

had been allocated for ports, of the addresses that people

were assigned. Jon, as editor of the RFCs did more than just

coordinate numbers, he wrote protocols. The File Transfer

Protocol, the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol, and Telnet were

just a few of the 232 documents that he authored.

Only at the end of the day, as I remembered what

Jon Postel had done for us, did the link to exploration

begin to become clearer in my mind. And, as I thought of

exploration, I kept coming back to the prayer wheels of

Tibet.

That evening, I changed my sendmail configuration and

installed an Internet prayer wheel in memory of Jon.

Every connection to our system to deliver mail is greeted

on port 25 by a standard banner message. I changed

that banner message to add a small prayer for Jon:

also% telnet invisible.net 25

connecting to host invisible.net (204.62.246.210), port 25

connection open

220 also.media.org; ESMTP Sun, 25 Jul 1999 12:39:46 -0400 (EDT);

For Jon Postel. Nature does not know extinction. All it knows is

transformation.

The prayer, like that in a real prayer wheel, is hidden. The

220 message, as Jon had recommended in his seminal RFC, is used when

one mail program connects to another on the SMTP port. Yet, every time the connection

is made, a prayer for Jon is sent upwards. It seemed like

a fitting tribute to a man who shunned the limelight, who wanted

only to make the Internet and the world under it a better place.

Om! Mane Padme Hum!

Reading List

Peter Hopkirk,

Trespassers on the Roof of the World : The Secret Exploration of Tibet

(Kodansha International, 1995). Hopkirk has written numerous books

about the exploration of Central Asia, but this one is my hands-on

favorite. Hopkirk tells of "the unholy spies of Captain

Montgomerie," the pundits of India, but he also introduces us to

a raft of other eccentric characters such as Henry Savage

Landor and Susie Rijnhart. Hopkirk does extensive research but

writes for a popular audience. Definitely recommended.

Rudyard Kipling,

Kim (Bantam Classics, 1983). Most of the world learned of the

Pundits from Kipling's classic novel. Though Kipling does go on

with his stereotypes of "asiatics" and "orientals," the story of Kim

is as touching as that of any Dickens waif.

Matthew H. Edney,

Mapping an Empire: The Geographical Construction of British India, 1765-1843

(University of Chicago Press, 1997). The other side of the

Pundit's exploration of Tibet was the systematic mapping of India

in the Great Trigonometrical Survey. The concept of India as a

single country, instead of a set of empires, city-states, and

wild areas, was largely a creation of the imagination of the British.

This scholarly book gives a fascinating look at route diaries and

at the internal politics of the Raj.

Hisao Kimura,

Japanese Agent in Tibet (Serindia, 1990). Sadly, this greatest

of all the adventure stories about strangers in Tibet is now out

of print. In 1939, Kimura spent four years in Inner Mongolia as an

agent of the Japanese government. To avoid conscription in the army,

he proposed himself as a spy, dressed as a Mongolian pilgrim, and

walked to Tibet. When he arrived in Lhasa, in September 1945, he

found himself "a spy without a master or a mission." So, he

walked to India, got himself a job with the British Secret Service,

and walked back to Tibet. Later, he learned how to smuggle gold,

became a trader on the roads to Lhasa, and finally returned to Japan

in 1950. Once home, Kimura became a leading scholar on Central Asia and was

instrumental in bringing Tibetan refugees to Japan for medical

attention and diplomatic training.

Thomas Pynchon,

Mason & Dixon (Henry Holt, 1998). To truly appreciate

the trigonometrical survey and the route diary, there is no

better book than Pynchon's amazing tale of the establishment of

the Mason & Dixon line by the eponymous

surveyors Mason and Dixon. This

massive yet highly accessible book goes from the clubs of Oxford to the

wilds of the American West with detours in South Africa and

the American South. Pynchon's treatment of automatons—the

high-tech toy of choice for that era—in the form of

a neurotic talking duck is nothing short of masterful.

|

|