|

|

E-Work

With open source the e-darling of today's e-press, it may strike many as heresy to say that the movement

lacks sustainability. In these days of disintermediation, melting borders, and death to old-line institutions,

some of my more libertarian colleagues may blanch when they hear it stated that the lack of sustainability

in open source is due to the lack of institutions. More institutions?

Gag me with a civil service manual!

If you listen to self-anointed open source popes (albeit gun-wielding popes) like Eric Raymond, author of

manifestos and the occasional snippet of code, what we are witnessing with miracles like Linux and

Apache is nothing less than a Revolution, an official Whole New Paradigm, the End of the World as You

Knew It. Microsoft will only be a memory and software will enjoy the

inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of packets.

If you listen to self-anointed open source popes (albeit gun-wielding popes) like Eric Raymond, author of

manifestos and the occasional snippet of code, what we are witnessing with miracles like Linux and

Apache is nothing less than a Revolution, an official Whole New Paradigm, the End of the World as You

Knew It. Microsoft will only be a memory and software will enjoy the

inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of packets.

I regularly attend the Reformed Church of Open Source and occasionally go to services at the ultra-orthodox Old Church of Free Software, but I confess I don't always believe that every program will be

saved if only it would strip off its compiler and walk naked through Comdex.

Open Source Miracles

The PC view these days is that Open Source is a self-sustaining system. Look at PERL. It was incubated by

Larry Wall at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, then moved into a somewhat fuzzy middle stage, and has

finally ended up as a stable, mature language supported by O'Reilly & Associates. O'Reilly sells millions

of dollars of PERL books, plus helps maintain the CPAN library and does a nifty yearly conference. PERL

is saved, the language (and libraries) are dynamic, and the language has a long-term future. It certainly

is an essential part of my computing infrastructure.

Or, look at Linux. Incubated by

Linus Torvalds and a huge cast of volunteers, the software reaches

millions of computers and is under active development. With companies like

VA Research selling Linux-based computers and

Red Hat

maintaining, supporting, and distributing an

operating system distribution, Linux is now in the mainstream.

Finally, look at two stalwarts of the movement, TCL and Sendmail. TCL was incubated at Sun and then moved into a fuzzy middle period where the future direction

was unclear. Now, TCL is a rousing success story at

Scriptics, which makes TCL widely available

and sells a great development kit called TclPro that features wrappers, compilers, and debuggers. Great

stuff! We bought TclPro and will be buying lots more copies.

Sendmail, the macro language we all love

to hate but all use, was incubated at Berkeley. The software has recently ended up in

Sendmail, Inc.

which keeps the base version widely available and sells value-added support and premium versions. I must

confess we haven't sent Sendmail, Inc. any money, but the possibility is certainly very real.

Open Problems

So, what's wrong? I would submit that the focus on the open source movement, with

Linux and Apache as poster children, is not addressing the problem. For every success story, there are

dozens of failures. One thing is apparent, however. We are witnessing the blossoming of a new

phenomenon at a level not seen in a long time: social entrepreneurs willing to put in huge numbers of hours

to make their community a better place.

This is not the first time we've seen this. For thousands of years, there have been periodic outpourings of

people willing to pitch in and improve their communities. Indeed, the Internet itself was built this

way. One can think that the Internet was the creation of NSF and ARPA and our brave private sector, but

the real reason the Internet didn't falter in mid-stream is that it was the product of an intense volunteer

movement. Thousands of people got day jobs in various capacities but made their real gig building

protocols (and implementations of those protocols) that worked. The Internet Engineering Task Force was

the meeting ground for this volunteer movement in the same way the Institute of Radio Engineers was the meeting

ground for the social entrepreneurs that built radio in the early part of the twentieth century.

But, it takes more than just human capital to build real, functioning services. The Internet lowers entry costs allowing

well-intentioned volunteers to start a new service with very little monetary

capital or computers or other expensive barriers to entry. But, when these enterprises become bigger, real resources are needed. The Internet means you don't need huge computers to start a service,

but when you reach millions of people, human capital needs to be supplemented with other forms of

capital.

So, what's wrong with the system adopted by Open Source advocates? Open Source is good for business.

Now that business understands that, everybody will live together in a happy coexistence. PERL is great for

business, lots of books get sold, the language is saved. Problem solved.

There are two problems with relying solely on human capital in the form of Open Source

hackers. First, the process is accidental. Sometimes it works, sometimes it goes dreadfully wrong. The

second problem is the process works fine for certain specialized, mission-critical software poster children,

but the focus on open source leads to the neglect of less glamorous but equally critical pieces

of infrastructure.

A Better E-Label

Open Source is a diversion from a broader class of programs: public works projects for the Internet. With

some trepidation, let me attempt to consolidate this concept into an e-trendy moniker: "E-Works" (not

affiliated with Ewoks or

STAR WARS in any way except in search engine results).

The E-Work concept is different from Open Source in that it

emphasizes the overall service provided to the community, not the fact that somebody wrote source code and

published it. PERL is an E-Work because it consists of a language and the things that make the language

useful: ongoing development, ports to multiple systems, training, books, and a community of users that

depend on PERL. By contrast, companies release the source code to a device driver for an obscure

product that only they sell (and which has no conceivable broader use), it may be open source but it certainly

isn't an Internet Public Works project.

Open Source defines its product by the fact that software is visible. Free software is defined by the fact

that the software is free. Public works means that a valuable service is being offered to the general public.

Think New York City. We need Bloomingdales and Macy's (and indeed these are part of the New York

community and do public projects such as the Macy's parade). But, New York also needs public works

projects like Central Park, Lincoln Center, the library, and parkways.

In the Internet, the focus on things like source distribution takes a focus away from a more important

criterion: is the service a useful one that increases equity and access for the public?

If you buy the global village metaphor, you have to buy the rest of this communitarian metaphor: we need a mix of public

and private activities on the Internet. PERL may be working, but look at the Domain Name System. The

NIC is now the intellectual property of Network Solutions and new top-level domains are being promulgated to

registrars that can meet very high entry costs. The only part of this essential service that seems to be

working well now is the informal operation of the root servers by a group of volunteers and the fact that the

BIND software is still widely available, thanks to the

Internet Software Consortium.

The Domain Name

System clearly isn't being run as a public works project and the U.S. Government, after an abortive attempt

by Ira Magaziner that was as successful as his efforts in health care reform, has become a primary stumbling block in

reforming the way our DNS is run. The DNS has been turned into the whipping boy for agressive corporate interest

groups hiding

under the shell of the

Internet Society and an

ICANN that seems overly

attuned to not making waves and keeping the Department of Commerce

stakeholders happy.

If you think that public works are well cared on the Internet, broaden yourself from source code to

data. After all, the whole point of software is to munge content. Look at the Federal Government, for example.

While some progress has been made in making core public information from the feds available to the

public, there is so much remaining to be done it is a true shame. The Patent and Trademark Office has been slowly getting itself

on-line, but the rest of the Department of Commerce seems to be pushing ever closer to a commercial

model where their data is a product, not a part of the infrastructure for the general public to build our cities

on. The retail information industry still rakes in hundreds of millions of dollars per year reselling

information that we already paid for with our tax dollars. That information

should be a lowest common denominator fundamental utility, a public good not a product.

The federal government's efforts to build an information economy infrastructure

of crucial data has been slow. Efforts by other

groups that should be building up these databases have been almost

non-existent (and highly unwelcomed by the relevant MIS departments in

the federal government when they do occur). Why? The barriers to entry are too high: you can

build an operating system with a few people, but it takes much more to

run a 500-gigabyte service with a user

population of several million page impressions per day. You also need a few

computers, a few T1 lines, and, unfortunately, a few lawyers to stay on top of misguided effort by federal

MIS czars to stop access.

Exit Strategy

In the business world, you start with an idea and some people willing to

take a risk and stand behind the idea. These are the "entrepreneurs,"

people with ideas and the energy to implement them. Those ideas are supplemented by financial capital, which in turn becomes resources

such as offices, computers, and all the other things a real functioning institution needs. The financial

capital comes from angels or venture capitalists, and the entrepreneurs have to convince these people that

they are building a sustainable operation that will have two ingredients:

- An ongoing stream of profits.

- An exit strategy.

The ongoing stream of profits means that the institution has sustainability. The exit strategy means

the investors can get their money back out, either through an initial public offering (e.g., sell their shares to

the general public) or through an acquisition (e.g., sell their shares to another institution, which may in turn

have sold their shares to the public or may be privately owned).

For Internet Public Works, we've witnessed a unique wave of entrepreneurs, people willing to put their

ideas and their time on the line to create something real. But, how to build these projects up beyond the

first stage? You can try to find a corporate sponsor who has an interest in the area, but I can tell you with 5

years of fund-raising for public works projects for the Internet behind me that the process is hit or miss. If

you can impress the corporation with the PR potential, you might win. But, you can't argue the merits of

why your public works project is needed for the public at large. That's just not good enough for corporate

money.

Sometimes things go really right, like with PERL; other times core software

just disappears or freezes functionality.

Look at multicasting, for example. Progressive service providers such as Verio are building

native multicast into their infrastructure. But, what about multicast applications that would allow anybody to start

doing collaborative audio and video across the Internet?

Multicasting started out just fine in the early stage. Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, ISI, Inria, UCL, and a

host of other groups provided the incubator stage, coming out with a whole slew of software systems such

as a whiteboard, video tools, audio tools, and session directory tools. Many of those efforts have now

stalled, as people leave their institutions and move on to other jobs. Where are multicasting applications

now? Cisco helped start up an Internet Multicasting Initiative, but the initiative is a classic industry group

with relatively high entry costs, a focus on high-priced conferences, and no attention to getting an essential

core of software tools available to the general public. The Internet Multicasting Initiative is building an

industry that can sell things like Cisco's IP/TV, but (like operating systems and Linux) there is a need for

ongoing development tools that are available to a broader audience.

Institutionalizing Open Source

If we need parks and schools and libraries, or their digital equivalent, then relying on

occasional wins when companies see immediate benefit in funding a public works project is haphazard.

Sure, we got lucky in the early part of the century when Andrew Carnegie decided the world needed libraries as

well as steel plants. But, what if there had been no way of funding other public works projects? Do you

think we'd have Lincoln Center if we had waited for Coca-Cola to sponsor it? Or Central Park? Do you

think New York would have had parks at the side of parkways if we had waited for the Ford Motor Company to

sponsor roads?

The Internet needs a more systematic way of encouraging the creation of public works. Let us posit

for just a bit that such an aim might be accomplished by an Internet Public Works Commission (or by many

such commissions). The goal of this commission would be to attract investment capital and manage that

capital by investing in a series of public works projects for the Internet that

maximize equity, access, and sustainability.

It is my contention that many of the current public works projects on the Internet, such as the Internet

Software Consortium, can certainly become sustainable enterprises in the long run, but requires capital

when they become middle-stage enterprises. How do we attract capital to the building of public works?

That requires a way to give the investors their money back, or else we are talking about donations, not investments. And, I can tell you definitively that

investment dollars come from a different pool (and a much larger pool)

than donation dollars.

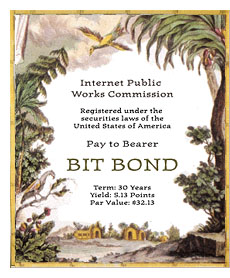

Here is one way to do this. The Commission is formed with a pool of capital, say $20 million. Perhaps this

comes from foundations. The goal of the commission is to attract another $200 million in capital from

investors who are interested in investing in Bit Bonds, a financial instrument that has a long period of

return (say 30 years) and is perhaps even guaranteed by the federal government, just as highway

construction bonds are often guaranteed by the federal government.

The commission takes this pool of capital and, with the help of a full-time staff drawn from both the open

source and financial communities, looks at the public works projects that have already been started. The criteria for investment might include:

- Do

any of these projects show the potential to move to the middle stage and become sustainable enterprises?

- Could

the commission invest in these projects and thus encumber the intellectual property so that it is always

available to the general public?

- Does the enterprise have a way of keeping going despite these intellectual

property liens?

- Do they have a management team willing to stick with the operation?

- Are there sources of

revenue, akin to the Museum Gift Store, that might be enough to sustain the operation?

In the case of the Internet Software Consortium, they were able to accomplish these goals. The investment

money came from a group of Unix vendors. The management talent came from hiring David Conrad, the

person who created the Asia Pacific NIC, as the executive director of the consortium. The ongoing support

came from selling support contracts to large corporations. However, as former chairman of the Internet

Software Consortium, I can tell you that getting to that point was not easy. Paul Vixie and I spent several

years before David Conrad was lured in and got things moving. During that time, ISC was not able to

advance the DNS to include security, build up the number of ports, or do any of the other special work

needed. ISC spent several-years in middle-stage purgatory before emerging successfully.

In many other cases, the projects just never made it. And, they never made it despite the fact that talented

engineers were willing to work hard on the projects and didn't really care if they might make more working

elsewhere. There just wasn't any place to find capital. This is not some assumption, this is based on

several years of getting email from people trying to figure out how to get their projects going.

How does this commission become more than just a donation? It only takes one web-like success.

Venture capital firms invest in dozens of firms, hoping one will make money. If you look at the dozens and

dozens of public works projects already on the net, it is highly probable that one of those will not only meet

the goals of equity and access to essential infrastructure, but might even make some real money for the

organization running it, and hence for the investors (including the commission). Just think how many hot

dogs are sold in Central Park. Do the commissions from hot dog sales take away from the park's general

mission? Not a chance. Is there an alternative? Sure, Central Park could have been designed as a

corporate sponsored park with admission fees.

Dodging Rat Holes

An Internet Public Works Commission would take a very special confluence of forces to happen, but it

could certainly happen. Investors with both vision and money would have to be convinced that the money

is managed in a way they'll get their money back on Bit Bonds. The staffing of the commission would have

to be done very carefully to make sure that these are people that understand what public works are and how

to work effectively with social entrepreneurs.

There is one easy way for such a project to go wrong, however and that is the dreaded Kitchen Sink

Syndrome. We need more artists on-line. Perhaps the commission should fund more artists. We need

more government data on-line and more people should know how to use it. Perhaps the commission should

sponsor training classes on how to use government data. Our schools have to be on-line. Perhaps the

commission should wire all the schools.

The key to a public works commission is focus. Investments in middle-stage enterprises that have

demonstrated they can move into sustainable operations with an investment in capital are the key. And, if

the commission is hard-headed in focusing on public infrastructure, many of the kitchen sink goals are

going to be easier to attain. Think public works, not a social incubator.

|

Stimulating Early-Stage Investment

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

But, there is one advantage of a middle-stage operation like the Commission.

This is what might be needed to stimulate the flow of capital from early-stage investors, like venture capital firms and angels.

Today, if you go to a VC with an idea for an Internet Public Works project, you have no exit strategy. With

no exit strategy, the person money sees a donation, not an investment.

What if a $200 million commission were making strategic investments? You can go to a VC and explain

your plan. Give me $200,000 and I will build essential public infrastructure up to 2 million page

impressions per day. I will then sustain the operation through a combination of revenue opportunities, and

fuel continued growth through an investment from the public works commission, which will also pay you

back your early-stage investment money. A $200 million commission could easily stimulate a $1 billion inflow

of capital from early-stage investors. Coupled with federal incentives, such as a hacker tax credit

which allows people to write off development costs for certain classes of open source projects, the foundations for a financial

system adequate for properly supporting the open source movement (and other public

works projects) begins to take shape.

What might a Public Works Commission invest in? I would hope that

this question would not be answered without some real e-work happening

first, but here are five categories of projects that are currently

underfunded:

- Open data. A huge amount of data, from libraries to government,

is being put on-line in a haphazard way. This must change.

- Operating systems. Any high-school teacher ought to be able

to down-load an OS, slap it on commodity PCs, and begin putting

together a network.

- Network configuration, control, and administration. The set top

box is one way to control your LAN, but you shouldn't have to

license technology from 12 different companies to set up, control,

and administer your computing devices, including your television,

your fridge, and all the other components that form your home

network.

- Core infrastructure. The DNS, the routing arbiter, root

servers, and a host of other key components are absolutely

essential to the proper functioning of the Internet and

these infrastructure components are being funded and operated

in a catch-as-catch-can manner. Big bad.

- Communications. Multicasting, IP telephony, radio on the

net, and IP/TV are all being developed as strictly commercial

products. Core applications (and support for those core

applications in the infrastructure) need to be much more

widely available.

Reinventing Government

Shouldn't the federal government be doing all this? Why bother with

intermediate institutions like a public works commission when our federal

government is sitting there looking for a mission in life when it comes

to building up the information highway? There is a well-known

phenomenon that

government can fund certain classes of work effectively, but is totally blind to others. Public works

projects in the real world are certainly supported by the feds but so far

our brave federal government silent has been incredibly silent on

the question of building real infrastructure. I tried to send e-mail

to Internet creator Al Gore, but he was busy

hacking some open source html on his

Hewlett-Packard Jornada.

In the real world, public works are created because a few citizens get together and decide that what their

community really needs is a park, or a library, or a museum, or a new parkway, or free concerts for

teenagers. Public works are local. The Internet doesn't change that, it

just changes the definition of what local is. It takes individual action to start

useful public works projects, and this proposal is an attempt to figure out a more systematic way to support

those individuals who have the willingness and ability to make public works

projects an

integral part of the Internet landscape. If we want an Internet composed

exclusively of shopping malls like Amazon and bedroom communities like AOL,

then nothing is needed. If we want to sustain the open source movement

and other public works projects, it is time for the revolution to grow

up.

We can wait for the federal government to build our communities, but they

are too busy reinventing their next election campaigns or preparing themselves

for the walk through the revolving door. We can wait for corporations

to magically build our parks. Or, we can do what communities have always

done: combine social capital with human labor and build ourselves the

kind of global village we want to live in.

If the Internet is a bedroom community, a place we go to make our

money and then exit after the gold rush, public works don't make

any sense. If we plan on living with this infrastructure for a long

time, it is time to start planning our infrastructure on a more

systematic basis that allows people to build the parks, schools,

libraries, and other public works that make our cities places

that last.

Copyright © 1999, 2000 media.org.

|

|