|

|

Topography

Many, if not most, types of mapped information can be clearly shown in two

dimensions: Political boundaries, population density, or annual rainfall

work just fine as flat areas of color. But a map that shows hills and

valleys can be extraordinarily useful to a cyclist in San Francisco or a

hiker in the Hindu Kush (though not, perhaps, to a skater in northern

Indiana).

Topographic maps address the problem of displaying three dimensions in

two. (The word derives from the Greek “topos,” “place,” and “graphein,”

“to draw.”) A topographical map shows the physical contours of a

landscape, including mountains, cliffs, gulleys, and plains, along with

features such as buildings, roads, ponds, and other landmarks.

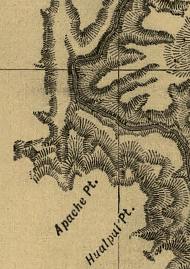

Early mapmakers depicted hills and valleys with shading or hatching, or

drew mountains as little saw-toothed profiles. Such attempts at

topographical information were of necessity crude, in part because there

was no standard to represent the data but also because the exact shape of

the features had not been measured. By the mid-19th century, improved

surveying provided more accurate information about the landscape;

contour lines became the convention for writing this information.

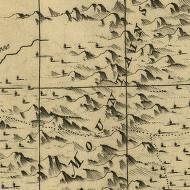

A contour line is simply a line drawn through a series of points that have

the same elevation. By drawing contour lines at regular intervals, such

as every 5 meters above sea level, a mapmaker can offer a reasonably good

representation of the lay of the land. On a topographical map a hill looks

like a bulls-eye of concentric circles, indicating a gentle slope, while a

cliff’s closely massed parallel lines show a steep one. Using the clues

provided by contour lines, a keen map reader can visualize the terrain and

pick out a level route or avoid dangerous drop-offs.

Another form of topographical map breaks the two-dimensional barrier and

extends into the third dimension. Such maps show the land's physical

shape in relief, with bumps for mountains and flat areas for seas. Though

more easily understood than two-dimensional maps, relief maps must be made

of rigid and unwieldy materials, which limits their portability. Still, a

relief map of, say, South America dramatically shows the relationship

between the Andes and the Amazon basin.

In such three-dimensional maps the vertical axis -- the height of the

features -- must be greatly exaggerated to show any relief. Though

mountains seem rugged to humans, they don't matter much on a global scale:

Mount Everest, the tallest peak, raises a bump smaller than one-seventh of

one percent of the earth’s radius. In other words, if you could hold the world in the palm of your hand, it would feel smoother than a billiard

ball.

Copyright © 1999, 2000 media.org.

|

|