|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

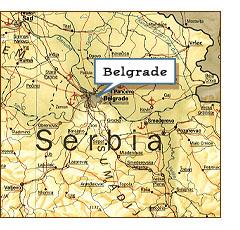

Keeping a map current is nearly impossible, especially when artificial features are involved. Buildings can be constructed or destroyed almost literally overnight, and even when they’re marked in the right place structures can be mislabeled. Errors like these can cause an international incident. Just ask Army Lieutenant General James C. King, who said to a reporter, “A hard copy map is outdated before it is printed.” King should know. He is the director of the National Imagery and Mapping Agency (NIMA), the government agency responsible for creating and updating maps used by the military. As a recent incident made abundantly clear, this is a critically important job. In May, 1999, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) selected 11 bombing targets in and around Belgrade, the capital of Yugoslavia, with the intent of weakening the power of Yugoslav president Slobodan Milosevic. One was an arms importing agency called the Federal Directorate of Supply and Procurement, at Bulevar Umetnosti 2 (Boulevard of the Arts), identified by the Central Intelligence Agency as having a prominent role in supplying arms to Slobodan Milosevic’s army. NIMA prepared a bombing map based on its information, experts plotted the coordinates, NATO planes dropped the bombs, and the mission went precisely as planned. There was just one problem. Instead of destroying the arms agency, NATO pilots hit the Chinese Embassy, killing three and wounding 27. “The attack was a mistake,” admitted Undersecretary of State Thomas Pickering in a presentation to the Chinese Government -- a map mistake. The US military had used three maps to find the target, two commercial maps and a NIMA map from 1997. All three were out of date and none specifically identified any building as the arms agency or the Chinese Embassy. Precision bombing requires exact coordinates for the target, so in what Pickering admitted was “a fundamental error,” coordinates were derived from known information. In other words, intelligence officers found the arms agency’s street address on the Internet and calculated its location by following the numbering system for buildings on parallel streets. As was later admitted, this technique was not designed to identify buildings as precisely as in this case; it’s a good way to get a rough idea of where a building might be, but not much more than that. Plus the Belgrade example is a classic case of, to coin a word, addressocentrism. In this country street addresses follow a consistent and systematic pattern; Americans would naturally assume this is standard. Typically, buildings in U.S. cities have sequential numbers, odd and even numbers are on opposite sides of the street, and so forth. But the rest of the world is not so consistent. In cities outside the U.S., buildings may be identified by numbering in the order in which they were constructed, or by counting sequentially down one side of the street and back on the other so the lowest and highest numbers are opposite, or even by giving houses names that the local letter carrier simply memorizes. Thus it was that those who extrapolated the addresses in Belgrade picked the wrong building. The Embassy and the arms agency are on the same street -- but the targeters failed to realize that its name changed at the intersection with Lenjinov Bulevar, or that an odd-numbered building could be on an “even” side of the street. Coordinates were plotted for the Chinese Embassy at No. 3, Ulica Tresnjevog Cveta (Cherry Blossom Street) instead of the arms directorate 300 meters away. A check against a database of sensitive buildings turned up no conflict, because the database was also outdated. (In Pickering’s words, “the databases in this case were wrong.”) A check of satellite maps showed no indications, such as flags or symbols, that the target building was an embassy, and nobody thought to check the address with anyone actually on the ground in Belgrade. One officer suspected that NATO might have the wrong building, but he didn’t know when it would be hit and by the time he got in touch with the military command it was too late. And so on May 7 a NATO B-2, flying at around 13,000 meters dropped five 2000-pound GPS-guided bombs on the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade. The bombs hit their target precisely, setting off an international firestorm.

China immediately accused the U.S. of having bombed the embassy on purpose. The “bad maps” story was rejected as being a cover-up for a deliberate assault on the People’s Republic and the murder of three of its intelligence agents. An apologetic US delegation to Beijing included Thomas R. Pickering, the Under Secretary of State, along with representatives of the Pentagon, the Central Intelligence Agency, the Defense Intelligence Agency and the National Security Council. To compensate for the damage, deaths, and injuries, the United States has given China $4.5 million. Nonetheless, the issue still simmers, straining relations and affecting relations in general, including the World Trade Organization negotiations. Conspiracy theories also continue to circulate, arising in part from a story in the London Observer (that is, incidentally, based entirely on anonymous sources). It seems much more attractive to think that the US would deliberately precipitate a dangerous international incident than that crack American strategists would make a stupid mistake, or more precisely, a series of stupid mistakes. And as a result of the incident, NIMA and the other agencies involved have undertaken an energetic program to make sure all maps and databases reflect current reality. But, as has been established, that could be difficult. The New York Times quotes an unnamed American intelligence officer as saying, “A worldwide database, even a database for a city the size of Belgrade or a country the size of Yugoslavia, is a daunting challenge to maintain…We can only do the best we can. And we can’t, you know, guarantee that something like this will not happen again.” Copyright © 1999, 2000 media.org. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|